Kong Meng San Meditation Centre

Contemplating the Meditation Centre

When we think of meditation spaces, the imagery is often of secluded pavilions nestled deep in the forest, or a solitary teahouse atop the hills. On this account, the Kong Meng San (KMS) Meditation Centre does not fit the archetype — it is a five-storey building situated within an urban context.

Contending with its scale and site, the design seeks to provide an environment conducive to meditation, and to evoke a non-sectarian ambience to appeal to a wider demographic, despite its religious setting amidst the KMS Phor Kark See Monastery. So, what are some universal qualities of space that allow the KMS Meditation Centre to transcend beyond its urban site and evoke a meditative state-of-mind? How can architecture reconcile a secular space for meditation within a religious complex?

Secular within Sacred

Taking the path through the monastery towards the Meditation Centre is a contemplative ritual; there is a sense of pilgrimage as one wanders along the open sheltered walkways adorned with traditional Chinese embellishments up a gentle hill, through the plethora of traditional Chinese temple forms and religious icons within the site. In contrast to its surrounding predecessors with their expressive finial structures and extensive adornments, the Meditation Centre is a cleanly carved single volume mass, wrapped tightly with a contiguous facade skin. The building is free from ornamentation, in line with its secular disposition. However, unlike some modernist religious buildings that are void of all traces of idioms in the pursuit of a pure, contemporary building, Founding Director of Forum Architects, Ar. Tan Kok Hiang MSIA, posits that it was crucial that the interpretation be connected to the historic site as well as share a visually coherent language to assimilate into the community of buildings within the monastery. This respectful approach sees the eaves of the building’s sweeping roof curved and upturned in traditional Chinese temple fashion. This vestigial element allows the building to strike a balance between the modern and the familiar, helping to establish kinship to the community. This delicate balance asserts the building as a product of our time, while contributing to the evolution of building typology in the monastery.

A Clear Plan

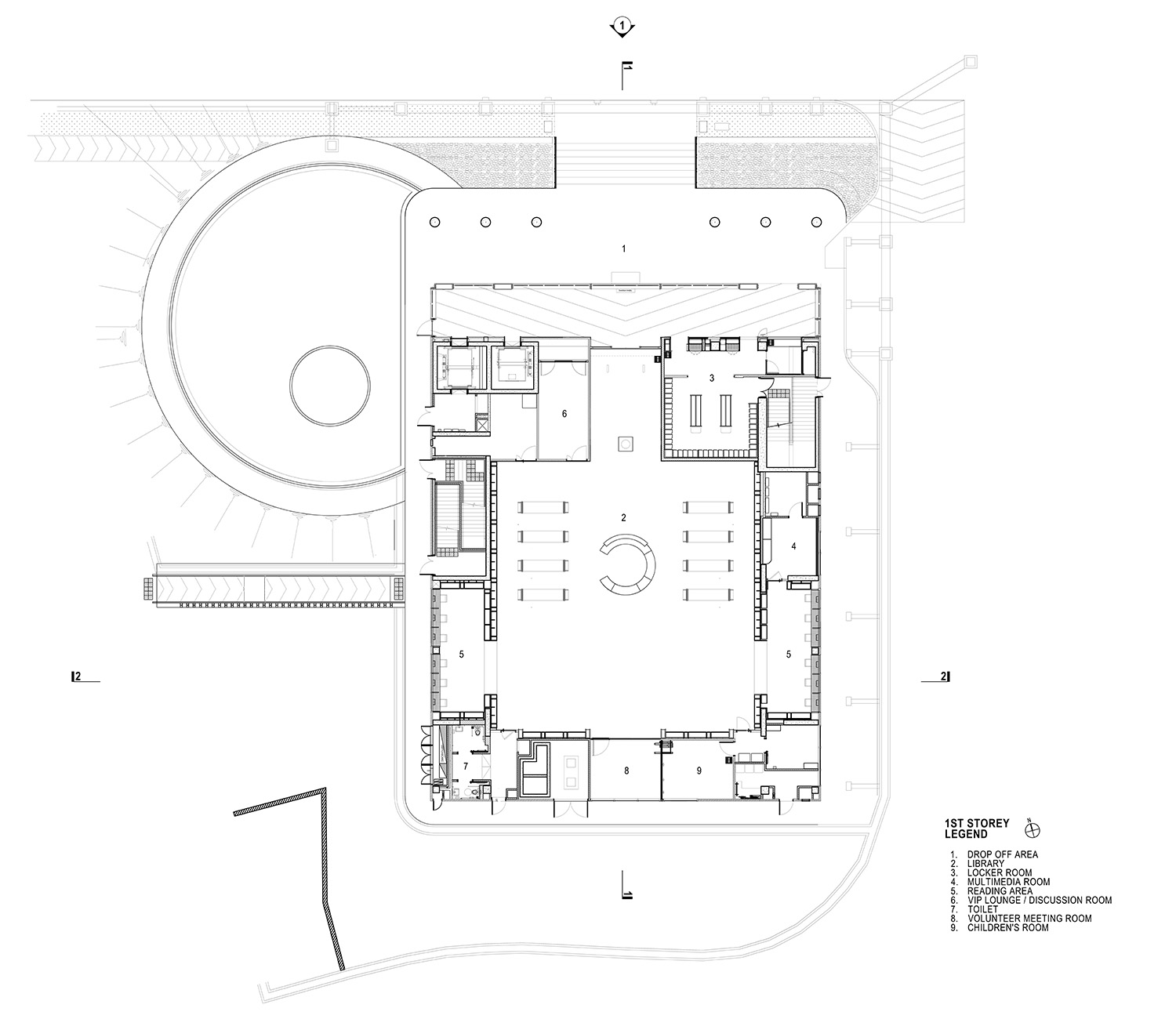

The building’s plan is clear and legible — a reflection of meditation’s strive for clarity. A strong symmetrical axis cuts through the orthogonal plan as an ordering principle, in the spirit of a typical traditional Chinese temple plan. The main programmes are a library, a main meditation hall, a series of smaller configurable meditation halls and the Sangha Meditation Hall. Sustained by the simplicity in function, the clearness of the plan extends to the section where each primary programme occupies a single floor by itself.

On each floor, the spaces are layered inwards from public to private — from the circulation verandas at the periphery, to the servant auxiliary spaces such as the lift cores, washrooms and staircases, and finally to the innermost heart of the building: the meditation halls. The large volume of the halls anchors the centre of the building as the surrounding servant spaces frame the cardinal spaces and act as a physical buffer to the elements, giving the plan a clear servant-served hierarchy.

As one journeys through the building to the main meditation hall, there is a series of curated spatial compressions and expansions. From the grand arrival at the main entrance foyer, to taking the lift upwards in a confined space, to transitioning past the high-volume lobby area, one finally enters a phenomenal domed ceiling hall, where the realm of meditation resides. The transition from external to internal is not only physical and metaphorical but manifested in the architectural details as the building begins to shed the punctuations and hard edges of its exterior façade, revealing white surfaces, curved ceilings, and contiguous strip lights to minimise distractions within the interior.

Apart from several beautifully restored intricate finials conserved from the demolished Dharma Hall, the interior is articulated by geometric forms and a restrained palette of whitewashed walls, timber finishes and bronze highlights. These subtle visual gestures achieve simplicity and cleanness of lines, eliminating sources of distraction for a clear mind.

Secular within Sacred

Taking the path through the monastery towards the Meditation Centre is a contemplative ritual; there is a sense of pilgrimage as one wanders along the open sheltered walkways adorned with traditional Chinese embellishments up a gentle hill, through the plethora of traditional Chinese temple forms and religious icons within the site. In contrast to its surrounding predecessors with their expressive finial structures and extensive adornments, the Meditation Centre is a cleanly carved single volume mass, wrapped tightly with a contiguous facade skin. The building is free from ornamentation, in line with its secular disposition. However, unlike some modernist religious buildings that are void of all traces of idioms in the pursuit of a pure, contemporary building, Founding Director of Forum Architects, Ar. Tan Kok Hiang MSIA, posits that it was crucial that the interpretation be connected to the historic site as well as share a visually coherent language to assimilate into the community of buildings within the monastery. This respectful approach sees the eaves of the building’s sweeping roof curved and upturned in traditional Chinese temple fashion. This vestigial element allows the building to strike a balance between the modern and the familiar, helping to establish kinship to the community. This delicate balance asserts the building as a product of our time, while contributing to the evolution of building typology in the monastery.

A Clear Plan

The building’s plan is clear and legible — a reflection of meditation’s strive for clarity. A strong symmetrical axis cuts through the orthogonal plan as an ordering principle, in the spirit of a typical traditional Chinese temple plan. The main programmes are a library, a main meditation hall, a series of smaller configurable meditation halls and the Sangha Meditation Hall. Sustained by the simplicity in function, the clearness of the plan extends to the section where each primary programme occupies a single floor by itself.

On each floor, the spaces are layered inwards from public to private — from the circulation verandas at the periphery, to the servant auxiliary spaces such as the lift cores, washrooms and staircases, and finally to the innermost heart of the building: the meditation halls. The large volume of the halls anchors the centre of the building as the surrounding servant spaces frame the cardinal spaces and act as a physical buffer to the elements, giving the plan a clear servant-served hierarchy.

As one journeys through the building to the main meditation hall, there is a series of curated spatial compressions and expansions. From the grand arrival at the main entrance foyer, to taking the lift upwards in a confined space, to transitioning past the high-volume lobby area, one finally enters a phenomenal domed ceiling hall, where the realm of meditation resides. The transition from external to internal is not only physical and metaphorical but manifested in the architectural details as the building begins to shed the punctuations and hard edges of its exterior façade, revealing white surfaces, curved ceilings, and contiguous strip lights to minimise distractions within the interior.

Apart from several beautifully restored intricate finials conserved from the demolished Dharma Hall, the interior is articulated by geometric forms and a restrained palette of whitewashed walls, timber finishes and bronze highlights. These subtle visual gestures achieve simplicity and cleanness of lines, eliminating sources of distraction for a clear mind.

Within and Without

Traversing along the naturally ventilated verandas, the articulation of the façade screens come into focus, revealing its their performative role beyond aesthetic. Internally, a row of glass louvres line and shield the building from the weather while allowing natural light and air to permeate through. Externally, a porous epidermis comprising of dense vertical rods of differentiated hues and sections wraps around and unifies the entire building. The three-dimensional screen mimics a thick bamboo grove, drawing inspiration from nature. Notwithstanding that being one with nature is a tenet of many meditation practices, the landscape is subdued both internally and externally. Perhaps, a metaphorical link suffices as the building stays true to its urban context.

Meditative Spaces

With meditation as its raison d'etre, creating a quiet and calm space is critical. Ar. Tan ruminates that calmness of mind is achieved by removing both external and internal distraction. Paradoxically, while external distractions can be eliminated by immersing oneself within a peaceful and uncluttered environment, the key to removing internal distraction is by focusing one’s attention on visual, aural or sensational stimuli. This is customarily achieved through the adoration of icons and the chanting of mantras etc.

Keeping in mind its secular nature, the meditation halls are clean and symmetrical; devoid of all features save a circular dome ceiling which creates a central focal point. The dome ceiling acts as an architectural device not only to create a singular focus by drawing the eyes upwards, to the centre but also has acoustic properties that captures and amplifies sounds within the space. Precisely calibrated diffused lighting enhances the atmosphere of the sanctuary and imbue the space with an ethereal quality.

Distinguished from the other meditation halls, the pièce de résistance is the Sangha Meditation Hall, which is exclusive to the monks. By virtue of its placement on the highest floor, the pavilion-like hall connects to the environment as natural light filters into the refined space. Surrounded by austere stone gardens against a backdrop of white walls, its elevated position and palette reflect the monk’s aspiration for enlightenment and provide ample privacy for meditation.

Conclusion

At first glance, the premise of a dedicated meditation building in highly urbanised Singapore conceived at the expense of the existing Dharma Hall may appear to be contrived, given that its context is neither nearly remote nor truly tranquil. However, KMS Meditation Centre debunks this hypothesisnotion;; through its nuanced form, clear layout and refined spaces, it re-affirms architecture’s ability to transcend beyond locale and religious faith to deliver a meditative experience. The building is a prime example of modern contemplative architecture that stands testament to the power of architecture in shaping our perceptions to induce a sense of peace and clarity, providing a respite for both mind and body.

Within and Without

Traversing along the naturally ventilated verandas, the articulation of the façade screens come into focus, revealing its their performative role beyond aesthetic. Internally, a row of glass louvres line and shield the building from the weather while allowing natural light and air to permeate through. Externally, a porous epidermis comprising of dense vertical rods of differentiated hues and sections wraps around and unifies the entire building. The three-dimensional screen mimics a thick bamboo grove, drawing inspiration from nature. Notwithstanding that being one with nature is a tenet of many meditation practices, the landscape is subdued both internally and externally. Perhaps, a metaphorical link suffices as the building stays true to its urban context.

Meditative Spaces

With meditation as its raison d'etre, creating a quiet and calm space is critical. Ar. Tan ruminates that calmness of mind is achieved by removing both external and internal distraction. Paradoxically, while external distractions can be eliminated by immersing oneself within a peaceful and uncluttered environment, the key to removing internal distraction is by focusing one’s attention on visual, aural or sensational stimuli. This is customarily achieved through the adoration of icons and the chanting of mantras etc.

Keeping in mind its secular nature, the meditation halls are clean and symmetrical; devoid of all features save a circular dome ceiling which creates a central focal point. The dome ceiling acts as an architectural device not only to create a singular focus by drawing the eyes upwards, to the centre but also has acoustic properties that captures and amplifies sounds within the space. Precisely calibrated diffused lighting enhances the atmosphere of the sanctuary and imbue the space with an ethereal quality.

Distinguished from the other meditation halls, the pièce de résistance is the Sangha Meditation Hall, which is exclusive to the monks. By virtue of its placement on the highest floor, the pavilion-like hall connects to the environment as natural light filters into the refined space. Surrounded by austere stone gardens against a backdrop of white walls, its elevated position and palette reflect the monk’s aspiration for enlightenment and provide ample privacy for meditation.

Conclusion

At first glance, the premise of a dedicated meditation building in highly urbanised Singapore conceived at the expense of the existing Dharma Hall may appear to be contrived, given that its context is neither nearly remote nor truly tranquil. However, KMS Meditation Centre debunks this hypothesisnotion;; through its nuanced form, clear layout and refined spaces, it re-affirms architecture’s ability to transcend beyond locale and religious faith to deliver a meditative experience. The building is a prime example of modern contemplative architecture that stands testament to the power of architecture in shaping our perceptions to induce a sense of peace and clarity, providing a respite for both mind and body.