Common Ground

Seeking Common Ground

We have seen in recent years the emergence and rise of a new typology of integrated town hub, in both new and mature HDB estates alike. These buildings, like Kampung Admiralty, Our Tampines Hub and the upcoming Buangkok Integrated Development are hyper dense in program and serve as a means to optimise land use by centralisation of public amenities. Consequently, in older mature estates, standalone community buildings become emptied of their former programme.

Such is the story of the former Bedok Public Library building - built in the 1980s and vacated two years ago when the Library moved into the neighbouring integrated community hub, Heartbeat@Bedok. The Library building itself is certainly a reflection of its time - modernist in aesthetic and built from reinforced concrete, but otherwise, fairly in its planning.

Enter The Thought Collective, a local social enterprise seeking a space to set up Common Ground – a civic centre meant to house various community partners under one roof, foster collaboration and drive innovation for social and community issues. As part of a testbed to study how ground-up social enterprises like theirs could transform the community, the Ministry of Culture, Community, and Youth (MCCY) provided The Thought Collective/Common Ground, with a grant to partially cover the cost of retrofitting and setting up within the building as its main tenant, with the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) Social Service Office as a sub-tenant.

Red Bean Architects (RBA), having already worked on three prior projects with The Thought Collective, were engaged to design Common Ground. The pairing of the project and the architect is aptly fitting as its principal, Ar. Teo Yee Chin, has long been a vocal advocate for the rejuvenation and reuse of older buildings in lieu of their demolition. The project demonstrates this conviction, while also addressing the question: How much does one need to do in order to renew a building?

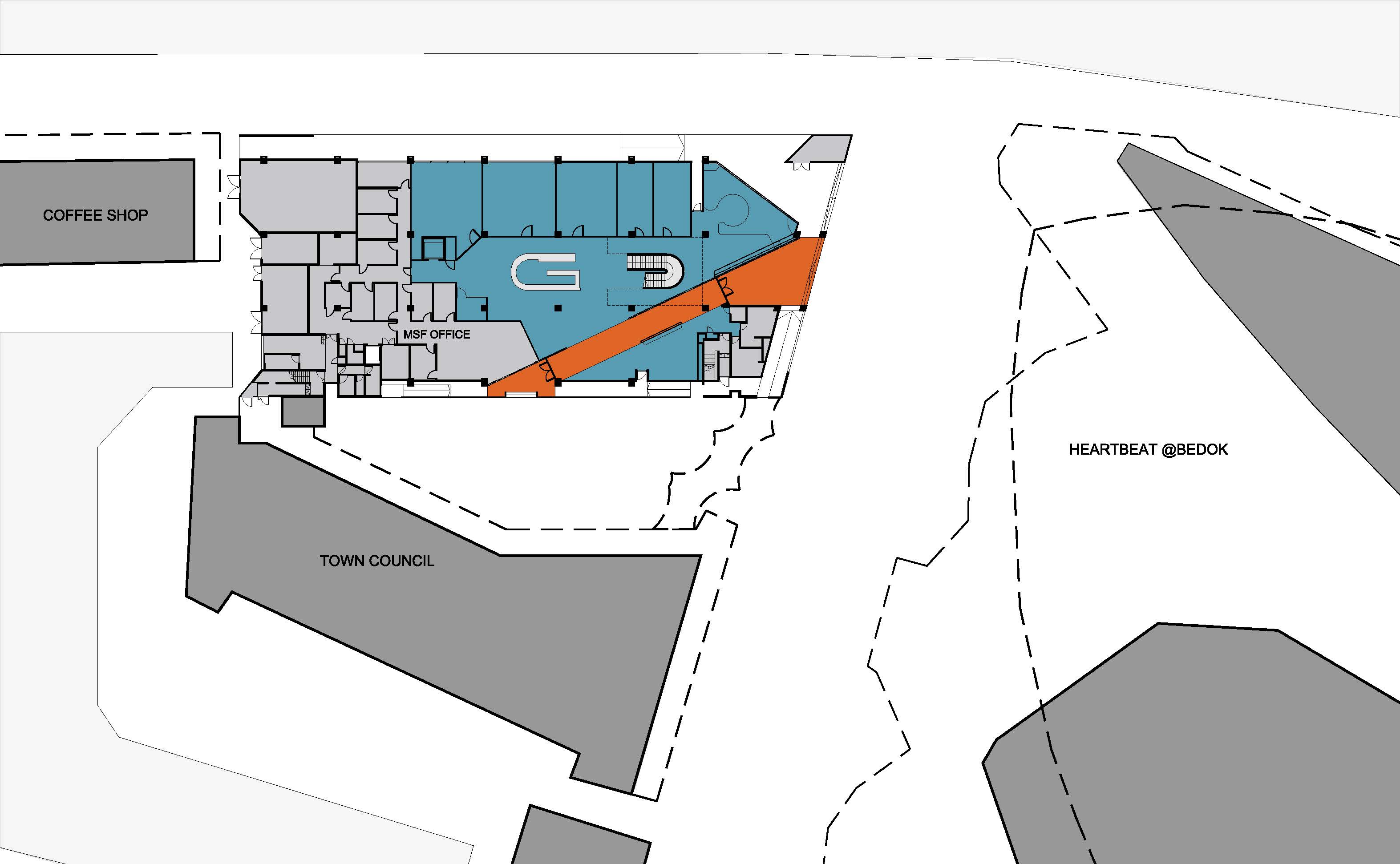

As a starting point, it was apparent that the building needed to be more open – both internally and to the outside community – to align with its new socio-civic program. RBA’s solution to this is one of minimal intervention. Conceptualised as a single diagonal cut across the building, this gesture does much heavy lifting to address competing needs from different occupants, draw missing connections to the site’s past and present context, and express the symbolic and functional aspects of its new programme, while supported by a tight budget.

At an urban scale, this cut forms a thoroughfare stretching from the original entrance that faces a quiet side courtyard off the main town centre promenade, to a new entrance along the promenade itself. This reorientation of the building’s frontage helps to reconnect it to the main spine of human activity while creating two separate and distinct entrances for the two organisations that shares the building. Common Ground was allocated this more public new entrance while the MSF Social Service Office was located closer to the more discreet original entrance.

On the exterior, the new entrance foyer is spacious and welcoming, recessed within the hefty volumes of the existing building. It is visually subtle with much of the exterior intentionally left untouched, save for a fresh coat of paint to give the facade an abstract and contemporary look. The humble material palette of terracotta floor tiles and vent block walls used to articulate the thoroughfare and entry allows it to blend into the context of the building - one would hardly realise that modifications had taken place at a glance.

Enter The Thought Collective, a local social enterprise seeking a space to set up Common Ground – a civic centre meant to house various community partners under one roof, foster collaboration and drive innovation for social and community issues. As part of a testbed to study how ground-up social enterprises like theirs could transform the community, the Ministry of Culture, Community, and Youth (MCCY) provided The Thought Collective/Common Ground, with a grant to partially cover the cost of retrofitting and setting up within the building as its main tenant, with the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) Social Service Office as a sub-tenant.

Red Bean Architects (RBA), having already worked on three prior projects with The Thought Collective, were engaged to design Common Ground. The pairing of the project and the architect is aptly fitting as its principal, Ar. Teo Yee Chin, has long been a vocal advocate for the rejuvenation and reuse of older buildings in lieu of their demolition. The project demonstrates this conviction, while also addressing the question: How much does one need to do in order to renew a building?

As a starting point, it was apparent that the building needed to be more open – both internally and to the outside community – to align with its new socio-civic program. RBA’s solution to this is one of minimal intervention. Conceptualised as a single diagonal cut across the building, this gesture does much heavy lifting to address competing needs from different occupants, draw missing connections to the site’s past and present context, and express the symbolic and functional aspects of its new programme, while supported by a tight budget.

At an urban scale, this cut forms a thoroughfare stretching from the original entrance that faces a quiet side courtyard off the main town centre promenade, to a new entrance along the promenade itself. This reorientation of the building’s frontage helps to reconnect it to the main spine of human activity while creating two separate and distinct entrances for the two organisations that shares the building. Common Ground was allocated this more public new entrance while the MSF Social Service Office was located closer to the more discreet original entrance.

On the exterior, the new entrance foyer is spacious and welcoming, recessed within the hefty volumes of the existing building. It is visually subtle with much of the exterior intentionally left untouched, save for a fresh coat of paint to give the facade an abstract and contemporary look. The humble material palette of terracotta floor tiles and vent block walls used to articulate the thoroughfare and entry allows it to blend into the context of the building - one would hardly realise that modifications had taken place at a glance.

Stepping into the inner confines of the thoroughfare is quite a visual spectacle made possible through a rich spatial experience spanning along the diagonal cut. Attention is drawn to the interplay of light and shadow between the periphery and the heart of the building, the dynamic perspective of the intersection between cut and atrium, the volume of the atrium and expanse of the floor. In short, it is at this point that you get a sense of the entirety of the building all at once.

The large aperture carved within the vent block wall functions as a framing device that offers multiple readings. When seen from the entry, it invites an appreciation of the existing staircase, revealing its surprisingly sculptural form that is a tense balance of weightiness and lightness. The vistas also create a sense of transparency in the interiors as they guide your eyes to the entrance, breakout spaces, landing areas of the stairs, and corridors. These seemingly mundane views are reflective of Common Ground’s ethos on conversation and collaboration - after all, interstitial spaces are often where chance encounters between people happen.

With all in that place, the space planning then comes very naturally. On the ground floor, generous break out spaces take up the heart of the building and spill into the main circulation route, encapsulating the spirit of community. Partner offices are lined up along the edge of the building to offer them a public front. The second floor is mainly delegated to MSF’s office – but quiet booths made from old library shelves can be found here for people needing some privacy. Lastly, on the third floor, the language of the diagonal is echoed here, forming a pathway that connects the administrative offices. The former children’s story-telling space containing an existing projection room, has been repurposed as an auditorium. This, together with the old library shelves, creates small call-backs to the history of the space.

The project displays a high level of efficiency and intelligence in making the most of a single architectural gesture: it provides a new contemporary identity to form that is also congruent with the existing, while also realigning it to a new context to ensure its relevance.

More importantly, it demonstrates that resiliency of our buildings lies in our attitude. RBA has approached this adaptive reuse with deep humility and sincerity by seeking value in the existing, engaging with it in a respectful but independent manner, while also working responsibly for its links to the wider context. This can be liberating in the way we may view our existing built environment - where recognition of its value relies on our own autonomous readings that need not necessarily conform with standard definitions of architectural merit.

What lies ahead for this humble project is to carry out its ambition of community engagement. While Common Ground welcomes all curious visitors to its building, COVID-19 has certainly made it difficult for these aspirations to happen. But I remain optimistic about its success. During the visit, we’ve noticed the neighbourhood uncle nestling up along the new frontage for an afternoon siesta. With one of the social enterprise partners, they’ve taken matters into their own hands by plastering posters from within their office to remind passers-by outside the building of their personal hygiene. In these small ways, the building is beginning to re-embed itself with the community.

Stepping into the inner confines of the thoroughfare is quite a visual spectacle made possible through a rich spatial experience spanning along the diagonal cut. Attention is drawn to the interplay of light and shadow between the periphery and the heart of the building, the dynamic perspective of the intersection between cut and atrium, the volume of the atrium and expanse of the floor. In short, it is at this point that you get a sense of the entirety of the building all at once.

The large aperture carved within the vent block wall functions as a framing device that offers multiple readings. When seen from the entry, it invites an appreciation of the existing staircase, revealing its surprisingly sculptural form that is a tense balance of weightiness and lightness. The vistas also create a sense of transparency in the interiors as they guide your eyes to the entrance, breakout spaces, landing areas of the stairs, and corridors. These seemingly mundane views are reflective of Common Ground’s ethos on conversation and collaboration - after all, interstitial spaces are often where chance encounters between people happen.

With all in that place, the space planning then comes very naturally. On the ground floor, generous break out spaces take up the heart of the building and spill into the main circulation route, encapsulating the spirit of community. Partner offices are lined up along the edge of the building to offer them a public front. The second floor is mainly delegated to MSF’s office – but quiet booths made from old library shelves can be found here for people needing some privacy. Lastly, on the third floor, the language of the diagonal is echoed here, forming a pathway that connects the administrative offices. The former children’s story-telling space containing an existing projection room, has been repurposed as an auditorium. This, together with the old library shelves, creates small call-backs to the history of the space.

The project displays a high level of efficiency and intelligence in making the most of a single architectural gesture: it provides a new contemporary identity to form that is also congruent with the existing, while also realigning it to a new context to ensure its relevance.

More importantly, it demonstrates that resiliency of our buildings lies in our attitude. RBA has approached this adaptive reuse with deep humility and sincerity by seeking value in the existing, engaging with it in a respectful but independent manner, while also working responsibly for its links to the wider context. This can be liberating in the way we may view our existing built environment - where recognition of its value relies on our own autonomous readings that need not necessarily conform with standard definitions of architectural merit.

What lies ahead for this humble project is to carry out its ambition of community engagement. While Common Ground welcomes all curious visitors to its building, COVID-19 has certainly made it difficult for these aspirations to happen. But I remain optimistic about its success. During the visit, we’ve noticed the neighbourhood uncle nestling up along the new frontage for an afternoon siesta. With one of the social enterprise partners, they’ve taken matters into their own hands by plastering posters from within their office to remind passers-by outside the building of their personal hygiene. In these small ways, the building is beginning to re-embed itself with the community.