Enter the Worlds

Text distilled from the paper “The Business of Spatial Transformations: The ‘Worlds’ Urban Entertainment Parks of Singapore” by Tan Kar Lin, first presented at the symposium Constructed Landscapes: Singapore in Southeast Asia, 2009.

A new urban phenomena emerging under the wary gaze of the colonial elite, the ‘Worlds’ exemplified the role of non-European private capital and enterprise in developing infrastructure, catalyzing city expansion, creating a mass leisure market, and forming a robust urban culture. They present a rich hybridity of urban typologies and cultural forms drawn from the migrant communities and influences that converged at the shores of colonial Singapore.

City fringe playground

Founded in the 20s-30s, the New World, Great World, and Happy/Gay World survived the Japanese Occupation, experienced a second boom during the Korean War, and began their slow decline in the 60s. They are commonly referred to as “amusement parks”, but here the term “entertainment parks” will be used instead, as a closer translation of their Malay name, taman hiburan, and Chinese name, %u6E38%u827A%u573A.

The ‘Worlds’ were located at what were originally the marshy fringes of the city - Jalan Besar (New World), Kim Seng Road (Great World), and Geylang (Happy World). Each was served by a trunk road, and land prices were just low enough so that a land-intensive enterprise like entertainment parks could be viable. At the time, the majority of the population was living in the city, so the ‘Worlds’ were just within walkable distance – by the standards of those days.

The show is on

The main draw at the ‘Worlds’ were performance-based entertainment or ‘shows’. There were theatres and pavilions, or semi-open stages, for bangsawan – a popular Malay opera, Chinese operas, Hindustani plays, gewutuan or revue troupes from China, getai or singing acts, and Malay ronggeng dancing. Some theatres were converted to cinemas, though open air screens were cheaper alternatives. The most ‘high class’ places were cabarets, with their big jazz band stands and grand dance floors. Attractions and programmes changed according to trends. In the postwar years, ronggeng dancing came into vogue, as did basketball, and the two main draws of the 50s – 60s were getai and trade fairs.

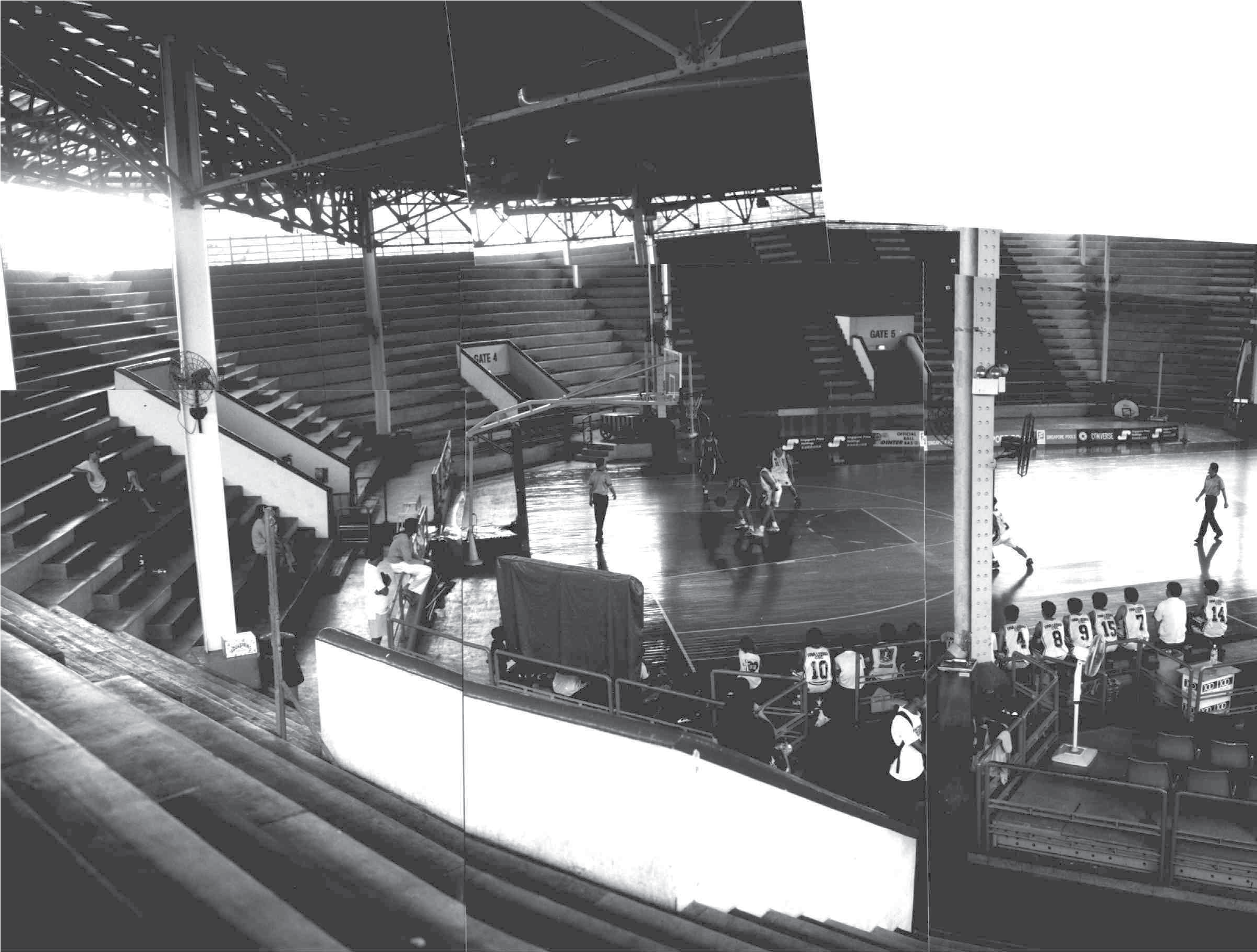

Sports was catered for in the form of open arenas with a grand stand, skating rinks, ball courts, or a stadium, with popular matches drawing large spectator crowds.

Amusement rides like Ghost Train or Ferris Wheel were imported. There were modern service providers such as photo studios and radio shops. The parks were peppered with places to eat and drink – grand restaurants, coffeeshops, beer gardens, and hawkers, and innumerable stalls selling sundries.

Apart from such stationed programmes, there were mobile operators like storytellers, buskers or matchmakers, who used the ‘Worlds’ as a captive base for their services.

The Singapore Free Press described the labyrinthine space in Happy World as a “maze of lanes” with “300 stalls“ devoted … to selling an amazing collection of goods and refreshments.” The spatial implication was that the layout of the entertainment parks were designed to maximise the number of stalls, and facilitate visitor circulation around them.

Stalls around popular programmes would fetch a higher rent, so these attractions, were distributed across the compound, each surrounded by ample circulation space, all lined with stalls.

More than just commercial playgrounds, the ‘Worlds’ hosted charity and community events, trade fairs and political rallies, especially in the post-war years. Though privately-funded, these parks played the role of a multi-purpose community infrastructure, at a time when the colonial government was reluctant to spend on public welfare. While Raffles Place and the Padang were domains of colonials and the rich, the ‘Worlds’ provided an urban, quasi-public space that cut across both ethnic and class boundaries. These were characteristics unique to the Malayan entertainment parks.

Form follows image

The image always took precedence in the architecture of the ‘Worlds’. The chameleonic quality of the spaces and buildings characterised the ‘Worlds’ as a whole, transforming and adapting to the times and trends, as and when necessary.

The Happy World Stadium, built in 1937, was the largest covered stadium in Southeast Asia, and the centrepiece of the park.

While a stadium today may be considered a purpose-built, specialised building for spectator sports or rock concerts, the Happy World Stadium has, through its 67 years of existence, been innovatively adapted for a wide range of functions by varying its layout and temporary installations.

During the 1939 Engineering Exhibition, timber gangways were put up along the tiered seating to become multi-level display galleries. In 1946, just after Happy World’s post war reopening, a projection room was erected in the stadium. Free movies were screened in a bid to win back visitors. By changing furniture arrangement, the arena was variously used for different exhibitions, and even hosting dinner events.

Buildings underwent extensive upgrading or rebuilding over the years. Sky Cinema in Great World which started as an open-air screening venue had a simple timber frame and tile roof shelter erected in 1948, fronted by a false art deco façade. In 1959, it was again redeveloped into a sizable purpose-built cinema in a flamboyant design by the firm Ho Kwong Yew & Sons.

The new building boasted novel ‘Cinerama’ technology with three projection rooms and a superwide curved screen. The grand opening was graced by none other than Elizabeth Taylor. Around the same time as Sky Cinema, the new Globe cinema designed by Gordon Dowsett was also completed.

Unlike tamer modern cinemas in town – Lido for example, Sky & Globe were a pair of loud, iconic structures, in line with the party town style of the ‘Worlds’.

Worlds’ end

The massive urban resettlement of the 60s-80s effectively emptied the city population to New Towns, removing the market base of the ‘Worlds’.

The new government was hard at work developing public infrastructure and amenities. The completion of the World Trade Centre in 1978 symbolised the end of the public role played by the entertainment parks in hosting trade fairs.

People wanted whole-day shopping and entertainment, not just at night when there’s a cool breeze. Rising expectations had to be met, and crowds shifted to new all-weather shopping centers, like People’s Park Complex.

Along with the ‘anti-yellow culture’ movement in the 1950s-70s, strict censorship rules were put in place. Striptease was banned of course, but so was open air cinema, for fear that it attracted illegal gathering. All performances had to submit scripts through a lengthy approval process, effectively a straitjacket for the live entertainment shows in the ‘Worlds’, which thrived on nimble programme changes and spontaneity.

The relaxed inclusiveness and creative energy that the ‘Worlds’ embodied was on the wane. It was about business right till the end, when it made more commercial sense to close down the ‘Worlds’ and sell the property for a good price. The ‘Worlds’ were always adept at changing to remain attractive and relevant. But transformations in the real world eventually rendered them obsolete.